Home

Home

About Geosun

About Geosun

Products

Products

- Hardware

- Mobile LiDAR Scanning System

- gCollector Road Information Collection System

- gSpin POS System

- PPK Solution

Support

Support

News

News

Contact Us

Contact Us

Nowadays, there are many Handheld SLAM LiDAR Scanner products available in the market. But what is SLAM? What is its purpose? And how can one choose a suitable Handheld SLAM LiDAR Scanner product? This article will provide you with the answers.

SLAM stands for Simultaneous Localization and Mapping. It consists of three key elements: simultaneous, localization, and mapping.

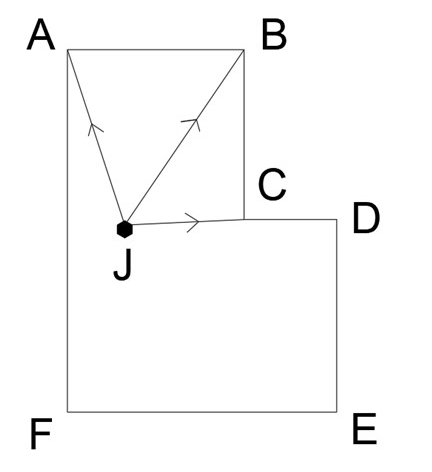

Localization is the process of determining the position of a device within a given map. Like GPS or total station positioning, SLAM localization measures the distance and angle between device J and known reference points (A, B, C) to calculate the robot's position.

Certainly, the simplified explanation of localization mentioned above does not cover an important aspect, which is the orientation or attitude (Roll, Pitch, Heading) of the device. The acquisition of these three values involves the transformation of coordinates between the sensor coordinate system and the map coordinate system, which can be understood as the rotational angles in the seven-parameter transformation.

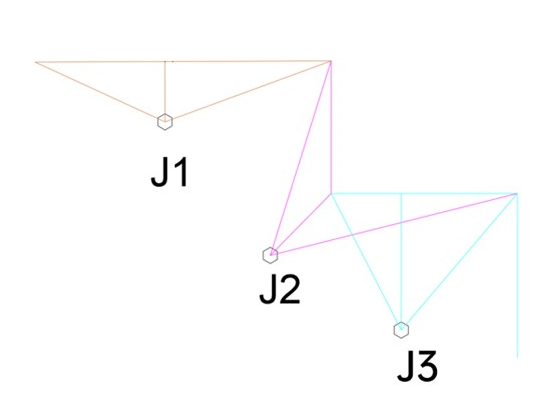

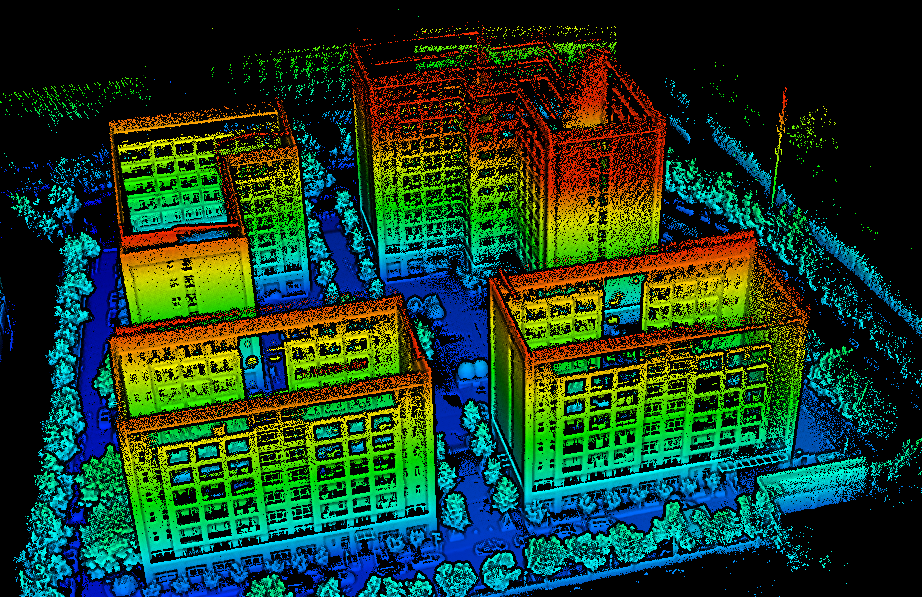

Once the positions and orientations (J1-J3 in the diagram below) of different locations are known, we can use a LiDAR scanner to scan the objects and obtain map data. This process is somewhat similar to the workflow of oblique photogrammetry, where accurate positions and orientations of photographs are determined (referred to as "space intersection"), followed by the three-dimensional reconstruction of objects.

Now you might wonder whether the map comes first or later. If the map comes first, we can scan the scene with known positions and orientations. But if we already have a map, why do the scanning? Furthermore, If we have a map, we can obtain our position and orientation, allowing us to scan the scene. However, the question arises: where does the initial localization come from? In outdoor environments, we can rely on GPS and IMU for localization. But in areas like underground corridors where GPS signals are unavailable, we need map data. Therefore, the above question is similar to the "chicken and egg problem".

This is where SLAM's "simultaneous" aspect comes into play. In simple terms, we can perform localization and map construction simultaneously. For example, imagine you want to explore a shopping mall in an unfamiliar place. First, you take a taxi to the mall's entrance and take a photo as a reference point. After having a preliminary understanding of the entrance and its surroundings, you enter the mall and go through the health registration process. As you explore each store, you establish connections between adjacent stores, noting their distances, spatial relationships, and your current location. By visiting all the stores sequentially, you gradually develop a holistic understanding of the mall's layout.

In summary, SLAM allows us to perform localization and map construction simultaneously. This is particularly useful in scenarios where initial localization is challenging or when GPS signals are unavailable, enabling us to explore and map unknown environments.

When considering a new device, it's important to understand its applications and potential uses. Here are three main application areas for handheld SLAM LiDAR scanners:

Handheld SLAM devices are well-suited for mine exploration due to the following reasons:

Due to the absence of GPS signals in mines, it is challenging to use RTK measurements.

Poor lighting conditions that may affect other measurement methods like total stations.

Narrow and complex mine passages, which make traditional total station measurements inefficient.

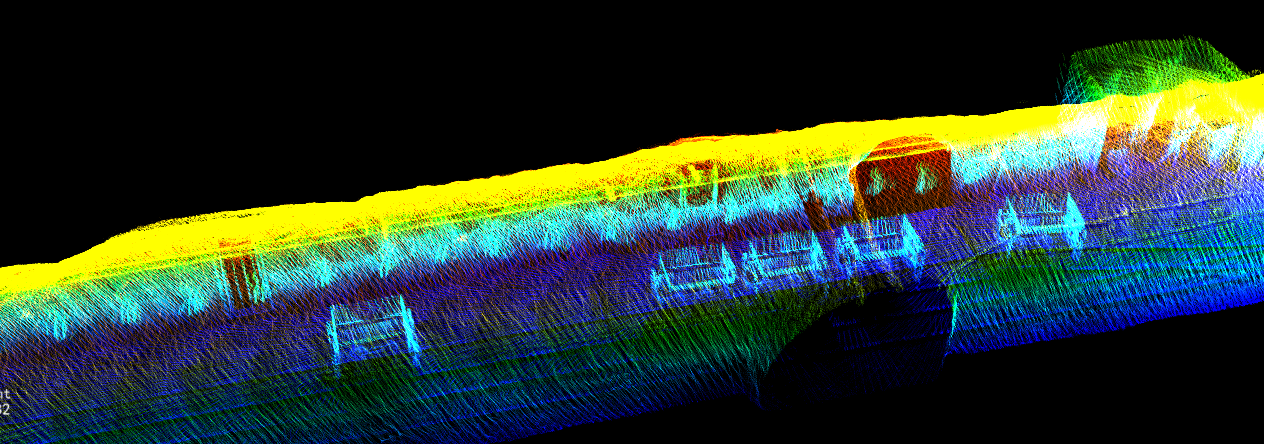

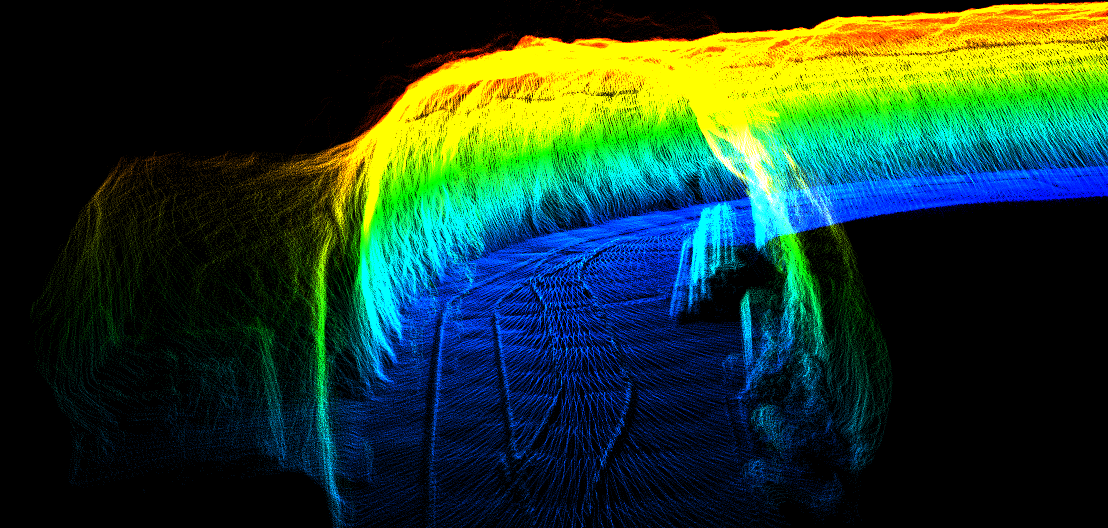

Given these challenges, handheld SLAM LiDAR scanners are particularly suitable for mines and geological caves, as they can perform simultaneous mapping while navigating without relying on GPS signals and are not affected by lighting conditions. The deliverables for mining applications using handheld SLAM devices include mine floor plans, cross-sections, volumes, and 3D models.

Traditional total station-based facade measurement methods have several limitations:

Traditional methods are time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring multiple people to collaborate during station setups, resulting in low efficiency during field data collection.

Traditional methods require high technical skills from operators.

Traditional techniques struggle to capture data effectively in scenarios with occlusions or obstructions.

Traditional methods cannot promptly identify data quality issues. If problems are discovered during subsequent data processing, additional field measurements are required.

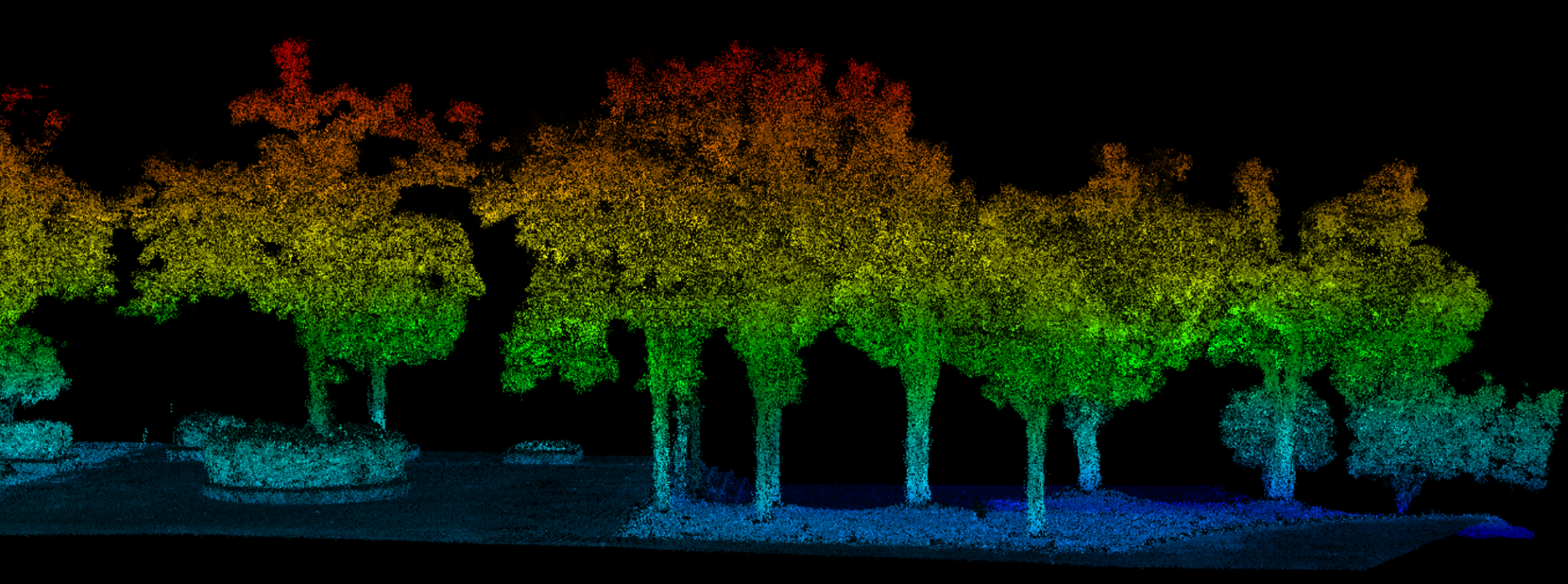

Although oblique photogrammetry techniques can measure facades through low-altitude aerial photography, they are ineffective in areas with no-fly zones or tree obstructions, limiting data acquisition.

Handheld SLAM LiDAR scanners offer advantages such as high efficiency, rapid data acquisition, and rich information (not limited to windows, doors, and openings). It can measure any scanned area, enhancing efficiency in subsequent data processing. Additionally, devices with panoramic imaging capabilities assist operators in identifying materials, signage, text, and other information.

The traditional RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) and total station technologies involve measuring individual points on objects to provide a rough description of the surveyed object. These measurements are then used with third-party software for earthwork calculations. However, the major drawbacks of using traditional methods include large point spacing, long fieldwork time, and low efficiency of RTK and total station techniques.

On the other hand, SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) technology does not rely on signals or the need for setting up and moving stations. It allows for extremely high point density (≥10,000 points/square meter). Whether it's the volume of an indoor or outdoor space, a transporting vessel, or the facade of a material storage bin, as long as the object can be scanned, volume measurement based on point clouds becomes highly convenient.

Other applications include underground municipal facilities, forestry, real estate surveying, parking lots, construction, geology, and more.

The first aspect to consider is the quality of the point cloud data. As a customer, you can judge the data quality based on the following factors:

Layering of point clouds: Layering refers to the misalignment or misregistration of point clouds acquired at different times in the same location during a scanning operation.

Thickness of point clouds: Thinner point clouds generally indicate better data quality, as thinner point clouds suggest superior algorithms. However, thinness does not refer to point cloud thinning, compression, or smoothing.

Relative accuracy: Relative accuracy refers to the dimensional accuracy and should be greater than the measurement range of the laser itself when verifying relative accuracy measurements.

Absolute accuracy: Currently, most handheld products on the market do not have GPS devices, so they rely on point marking to convert relative coordinates to absolute coordinates. The validation of absolute accuracy requires the deployment of reflector targets (such as 3M reflective stickers) on-site or the use of road markings as checkpoints.

Product design can be evaluated based on the following aspects:

Stability: Stability refers to the stability of data acquisition and the device's ability to withstand harsh conditions (e.g., no device crashes or malfunctions). This assumes proper operation according to the manufacturer's instructions and in compliance with established procedures.

User-friendliness: The design should be simple and easy to use, with considerations for comfortable handling.

Ease of maintenance: The device should be easy to maintain, allowing for convenient repairs and servicing.

The key factor in evaluating a handheld SLAM device lies in the quality of its data. Therefore, when selecting a product, it is crucial to conduct thorough testing and rely on practical experience.

URL:https://www.geosuntech.com/News/224.html

Previous:Understanding RTK Positioning: A Comprehensive Guide

Next:Comparison of LiDAR and Photogrammetry Technology in Drone Mapping Applications